It has been twenty days since the dawn of Ramadhan, and as a type 2 diabetic, the prospect of fasting looms like a shadow over my fragile health. The fear of hypoglycemia, of my body shutting down without warning, gnaws at the edges of my resolve. Yet, against all odds, my body has held its ground, weathering the hunger shocks with a quiet resilience. My mind, however, is a tempest of thoughts—fleeting, fragmented, desperate to be captured in ink but evaporating like morning mist the moment I reach for them. Now, back in my kampung for Ramadhan, I find myself drawn to the memories of my childhood, a time both bitter and sweet, etched into the very soil of Kg. Dangar.

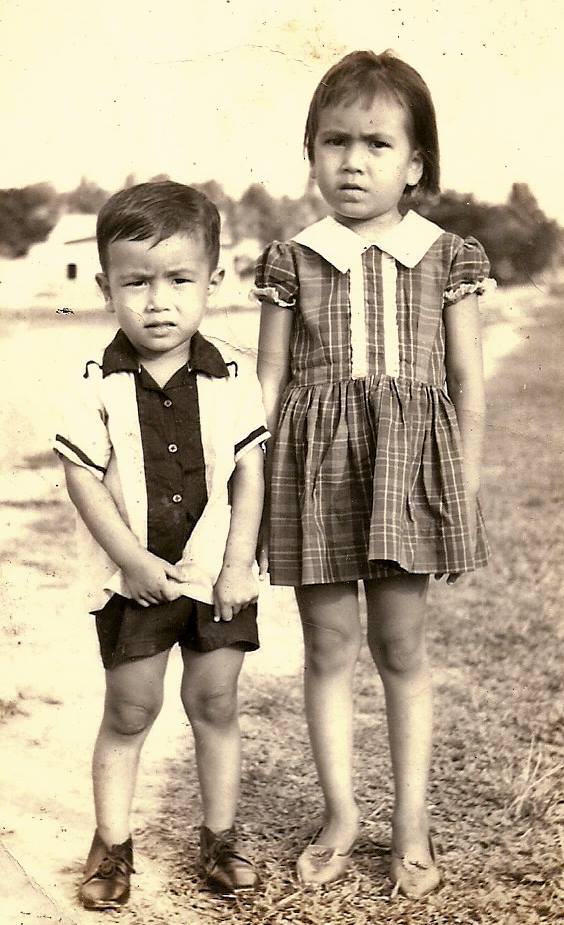

I grew up in the suburban embrace of this small town, a mere fifteen-minute walk from the town center. The house where I spent most of my childhood still stands, though it now belongs to my sister. In the 60s and 70s, poverty was the common thread that bound us all, save for the royals and a handful of government officers. My family was no exception—dirt poor, with parents who toiled at odd jobs to bring home just enough food to feed their twelve children. I often revisit those days, not out of nostalgia, but to commemorate the hardship that shaped me. I try to summon the emotions of that child I once was, to feel the weight of his sorrow, but the memories are elusive. Perhaps a child is too naive to mourn what he never had. The absence of toys, a bicycle, even a bed of my own—these were concepts too abstract for a mind unburdened by the weight of possession. Poor kid, indeed.

One day, Ayah dropped me off at school on his way to work, and thus began my academic journey—a lifeline I would cling to for the next fifty-five years. The school was only five minutes from home, a place both terrifying and exhilarating. Sports, in particular, were my nemesis. They stripped me of my humanity, reducing me to a useless, gasping heap. My frail body, devoid of muscle, turned a hundred-meter dash into a marathon of humiliation. The finish line might as well have been a mirage. To me, sports were not a test of skill but a cruel exhibition of my inadequacy. My strategy for survival? Avoidance. And so, I became the “sissy boy,” or pondan, as they called me in Malay—a label spat with disdain by both classmates and teachers alike. Yet, I wore it like a badge, unflinching, unmoved. Poor kid.

My world revolved around Kg. Dangar, and at its heart was Nik Adnan’s shop. He was a man in his twenties then, newly married, with a temper as volatile as the monsoon winds. One moment, he was all smiles; the next, he was screaming at the top of his lungs because I dared touch the lid of his biscuit jar. I ran home that day, vowing never to return. Decades later, we crossed paths at my brother’s wedding. He reminisced about the old days, and we laughed. Funny, how time softens even the sharpest edges of memory.

One of the most cherished memories of my childhood was the walk to Grandma’s house in Pondok Pak Su Wein, a religious compound led by the eponymous teacher. The journey took us through a rubber tree orchard, where we would pause to collect rubber seeds, the afternoon sun filtering through the canopy above. The shade was a welcome respite, and the forest that followed felt like a gateway to another world. At Grandma’s, we were always greeted with treats—food, pocket money, or simply the warmth of her presence.

Now, when I visit Kg. Dangar, I am a stranger in my own past. The children I once knew have grown into adults, their faces unfamiliar. Some of my primary school friends might still linger here, but it has been forty-eight years since I left. The threads that once connected us have frayed with time.

Despite the trials of school, I loved it fiercely from 1972 to 1976. Bahasa and Science were my favorite subjects. I remember the day I built a telescope during our lesson on light, marveling at how it inverted the world. I was so proud to show it to my teacher, but he dismissed it with a grimace, the paper smudged with the cooking oil I had borrowed from Mom. English class, however, was a different story—a living hell. As a kampung boy, English felt like an alien language. My teacher’s slap became a cruel punctuation to every incorrect answer, his perfume a trigger for the trauma that haunts me to this day. May he burn in hell, for all I care.

In 1977, I left for boarding school, a year earlier than my peers. The transition was brutal. I became the target of relentless bullying, isolated and terrified, with no one to turn to. The years that followed were a blur of fear and loneliness, a chapter of my life I would rather forget. Yet, here I am, still standing, still remembering. Kg. Dangar may no longer recognize me, but its stories are etched into my soul, a testament to the boy who once called it home.